Healing & Reconciliation Through Education

As part of Phase One of the Reclaiming Shingwauk Hall Exhibition Project an Integrated Curatorial and Design Plan comprising the narrative arc of the exhibition was developed. The proposed narrative follows a journey – as visitors enter the Algoma University grounds, pass through the entrance to the Shingwauk Auditorium, continue down the hall, crossing the threshold into the vestibule, through to the auditorium itself to navigate the exhibition’s pathways. This storyline, which has been broken down into six zones, was developed for consideration and discussion with the various stakeholders and was informed by discussion and interviews with representatives of the Shingwauk Indian Residential Schools Centre, Shingwauk Kinoomaage Gamig, and Algoma University, June 26-27, 2014 and was presented at the 2015 Shingwauk Residential School Gathering.

This narrative arc does not create a linear narrative. Rather it examines stories at crossroads and points of convergence through layer-making and juxtaposition.

![]()

Shingwauk Auditorium (Opening 2021)

Curators: Jeff Thomas and Jon Dewar

Thematic Description: This space witll explore the intersections of visual artists and the arts in the healing movement. This may mean exploring Zone 4-6 through the visual arts and could also involve producing art through participatory workshops that will go on exhibition as a supplement to the permanent exhibition content. For each zone, might have two text panels, works of art with descriptive captions, and space for a number of workshop generated art works and associated stories/captions.

Section 4.i. The Indian Residential School system in Canada

Approach: This sections looks at how photography was used to promote federal support for an Indian residential school system – connections with Carlisle Industrial school are explored here. The structure may be roughly divided into four sections. Section A interrogates the notion of the ‘vanishing Indian’ through a series of images of children before entering residential schools, and during their tutelage. It asks: What kind of Indians are they? A photograph of Hayter Reed, Indian Agent and later Deputy Superintendent of Indian Affairs, dressed in tribal regalia beckons our close attention to the contested practice of cultural appropriation. Section B implicates visitors in reflecting their image back to them in superimposition with a late 19th century photographic studio set, asking in response to: What kind of Indians are they?, What about you? The set invites visitors to stage and share their own self-portrait in response to the exhibition questions. The ‘selfies’ generated by the exhibition are then displayed in a digital gallery on an interactive screen on the perpendicular wall. The interactive screen will also display the artworks produced in the workshop.

Section 4.i. Sections C and D ask visitors to consider late 19th and early 20th century understandings of needs of children in relation to their education, contrasting Indigenous perspectives with Euro-centric ones. Perspectives on children’s needs are explored through objects that convey cultural value, from medicine bundles to protractors. The objective of this section to highlight the epistemological and corresponding cultural differences that contributed to the failure of the Indian residential school system. Artwork: Archival images of Thomas Moore (Sessional Report images), Hayter Reed, and selected images from archives from the Carlyle Indian Industrial School Workshop: Decolonizing through Images – participants will create original storytelling works by juxtaposing historical and contemporary photography in a collage format. The works and descriptive captions will be mounted on rotation.

Section 4.ii. Indigenous Boarding Schools Around the World

Approach: This section uses artwork drawn from various countries to explore the international context. Imperial/ expansionist rhetoric including the concepts of ‘manifest destiny’ and the ‘white man’s burden’ will also be critiqued.

Section 5.i. Social upheaval and social and political struggle and movements including the American Indian Movement (AIM) and the National Indian Brotherhood (NIB). Also, this section will explore the winding down and closure of the IRS, the 60s scoop, reports of abuse, litigation, the IRSSA settlement, Federal and church apologies, and subsequent attempts at redress including the TRC.

Approach: This section explores a chronology of events over a period of massive change. A timeline will be used to contextualize events. Artwork: The timeline will be illustrated with Indigenous artworks and Indigenous and non-Indigenous arts and curatorial collaborative works, expressing resistance and resilience. Artists featured may be: Adrian Stimson, Chris Bose, Leah Decter and Jaime Issac, Carl Beam, George Littlechild [esp pictographs similar to those produced at the Carlisle school] Tanya Willard, Peter Morin, etc.

Section 5.ii. cultural revitalization – including language revitalization, decolonization, and healing (in Canada and in world Indigenous healing movements) in general, but also the work of the Children of Shingwauk Alumni Association and their long fight with Algoma for the Shingwauk Trust Land. Approach: This section examines the connection between culture and healing. A series of 5 to 7 integrated interactive sound cones will individually project recordings of sentences or phrases in different Indigenous language for visitors to try to repeat. Upon hearing the phrase, visitors will attempt to repeat it into a microphone situated in the cone. Using sound recognition software, the percentage corresponding to the degree of accuracy of the phrase reproduction will be generated and projected onto the interior surface of the cone for the visitor to view. This activity highlights the difficulty of learning a foreign language, which the students of the Shingwauk IRS would have faced upon entering the school. Artwork: local works produced or commissioned by the SRSC.

Section 6.i. This section explores the importance of identity, first by focusing on Survivor Shirley Williams and how her identity was stripped from her through the dehumanizing experiences she experienced at residential school. Next, this section looks at regaining and reclaiming identity not only through revitalizing cultural identity but by creating new, contemporary, and hybrid identities – redefining what it means to be Indigenous in a contemporary context. Artwork: Photographs by Jeff Thomas, Rosalie Favell, as well as a profile of Walking with Our Sisters, a project that through moccasin vamps, represents the lives and identities of the countless Indigenous women and girls [and babies] who are missing or have been murdered in Canada. Workshop: Participants will use symbolism meaningful to them to create a self-portrait that reflects their identity.

Section 6.ii. This section looks at barriers to education and profiles what is taking place today at Algoma University and Shingwauk Kinoomaage Gamig to overcome barriers, restore cultural identities and practices, and strengthen Indigenous communities. This will be discussed in the context of restoring Shingwauk’s vision. Approach: This section will presented through the stories of youth role models for education. The stories will emphasize overcoming barriers and changing attitudes toward education. Artwork: Portraits of Anishinaabe students young and old. Objective: To explore the aforementioned themes through existing and programming generated artistic expressions.

![]()

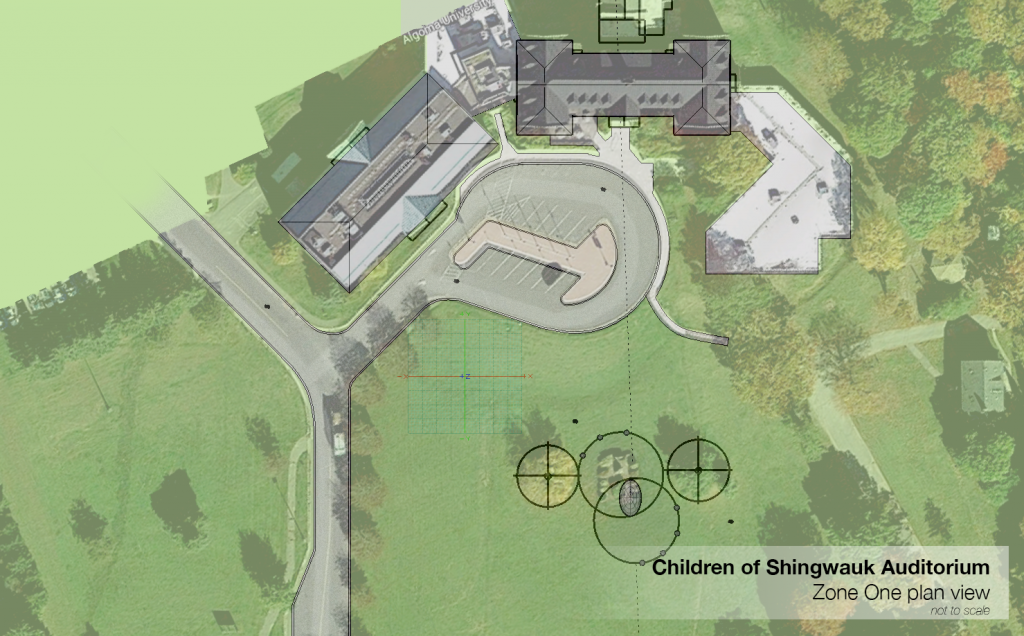

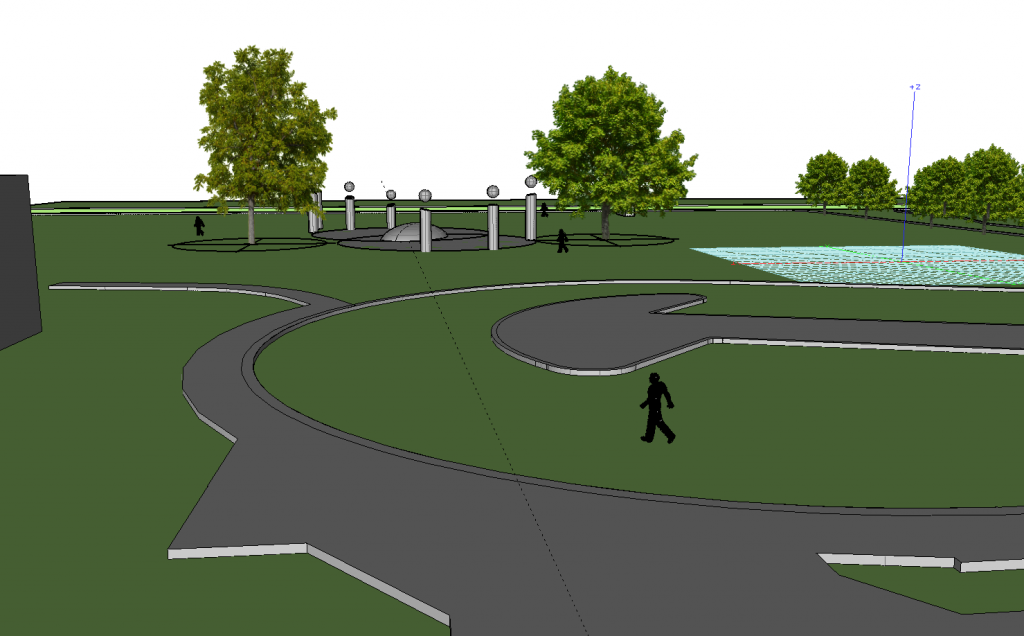

Shingwauk Site Grounds (proposed)

Curators: Jeff Thomas and Jon Dewar.

Thematic Description: Using the seven sacred fires prophesy as a framework, this section will tell the history of Turtle Island and the Anishinaabe, traditional ways of life in all its diversity, contact with Europeans, settlers, and religion, through to the arrival of children from different Nations to the grounds of the first Shingwauk and Wawanosh schools and experience.

Objective: To orient the visitor around Indigenous history and epistemology, to ground the story in the land, to contextualize the IRS within a much more expansive history and sense of time.

Narrative, Voice, and Form: Storytelling in recorded audio juxtaposing the voices of Elders (x7) who will tell the prophecy and children (x7) who will describe their lived experience in the time of each prophecy coming to fruition.

Design Concept:

The ceremonial circle will consist of 7 tree-like corten steel columnar structures. Each of the columns will feature an inset cylindrical tempered glass candle/fire ‘lantern’ unit that will produce a vertical flame visible through a laser-cut filigree design representative of each of the seven sacred fires prophecy. Each laser-cut design will reflect the aesthetic vocabulary of the appropriate Indigenous arts style or movement, for example, one or more may be executed in a Woodlands style. Through an aperture in the filigree, visitors will be able to make tobacco and other offerings.

- The column surrounds may be designed to mimic fire pits, making use of local river rock.

- Benches interspersed between the columns will provide seating and will be made wheelchair accessible.

- The surrounding area may be landscaped using local Indigenous plants and medicines.

- On the grounds, at appropriate sites adjacent to the sacred fires circle, one or multiple circles of open areas may be leveled and demarcated through landscaping as sites for sweat lodges to be temporarily/seasonally constructed. Large movable fire bowls or pits may be placed into proximity to provide the opportunity to create, tend, and keep the fires and heat the stones necessary to hold sweat ceremonies. After the sweat lodge has been dismantled and the fire bowl or pit stored, the site remains a sacred ceremonial space.